Exercise physiology illustrated

Bro, do you even lift ?

-> Hmm🫣, I guess?

Over the years, I've followed a few workout programs with varying degrees of effectiveness, and none really lasted any longer than a season of training. Recently I noticed what I had been doing so far was mostly following "methods" without understanding the underlying "principles". Most programs were telling me what to do but not why. And if you think about it, exercises, rep counts, target sets, meal plans are human inventions. They exist at the macro level. But at the micro level, my body's cells have no idea what a 3x12, leg day, or cheat meals are. They only respond to signals they receive.

Until I understood what happens at the physiological level, training felt like a black box. I was basically trusting (or rather hoping) that whatever a program promised would indeed apply to me. When it didn't work, I didn’t know why; and when it did, I didn’t know why either. And sooner or later I’d lose motivation and chase the next trendy method. Everything changed when I shifted my focus from following methods to understanding principles. I now feel much more empowered to design my own training based on my improved knowledge of the human body.

While researching, I was surprised how little scientifically up-to-date and easily digestible content exists, much of it is either buried in dense textbooks or oversimplified into bro-science. One resource that stood out for me was Kyle Boggeman’s (Kboges) work—he breaks down the scientific literature into practical and digestible insights. I learned a lot but was missing the visual dimension which is so dear to me. So I created my own illustrated version based on his work and my own research.

Quick disclaimer: I'm not an exercise professional - just an anatomy & physiology nerd who likes to put complicated concepts into engaging visual stories. I hope that this article will help more people understand their body better and feel more empowered when thinking about training.

Here are the key questions I'll address in this post :

- How to cultivate an athletic body (healthy, strong and aesthetic)?

- How does the body build muscle at the cellular level?

- How does training generate the muscle growth signal?

- What type of training is suitable for hypertrophy and strength?

Let's dive in.

Part 1: Understanding the physiology of physical adaptation

My main goal with training is general athleticism, meaning that I want my body to feel good (health), look good (aesthetics) and perform well (strength, agility etc.) in whatever activity life throws at me. This isn’t about extreme longevity, bodybuilding or performance - just balanced, sustainable athletic development.

How to improve athleticism?

-> By changing the body composition.

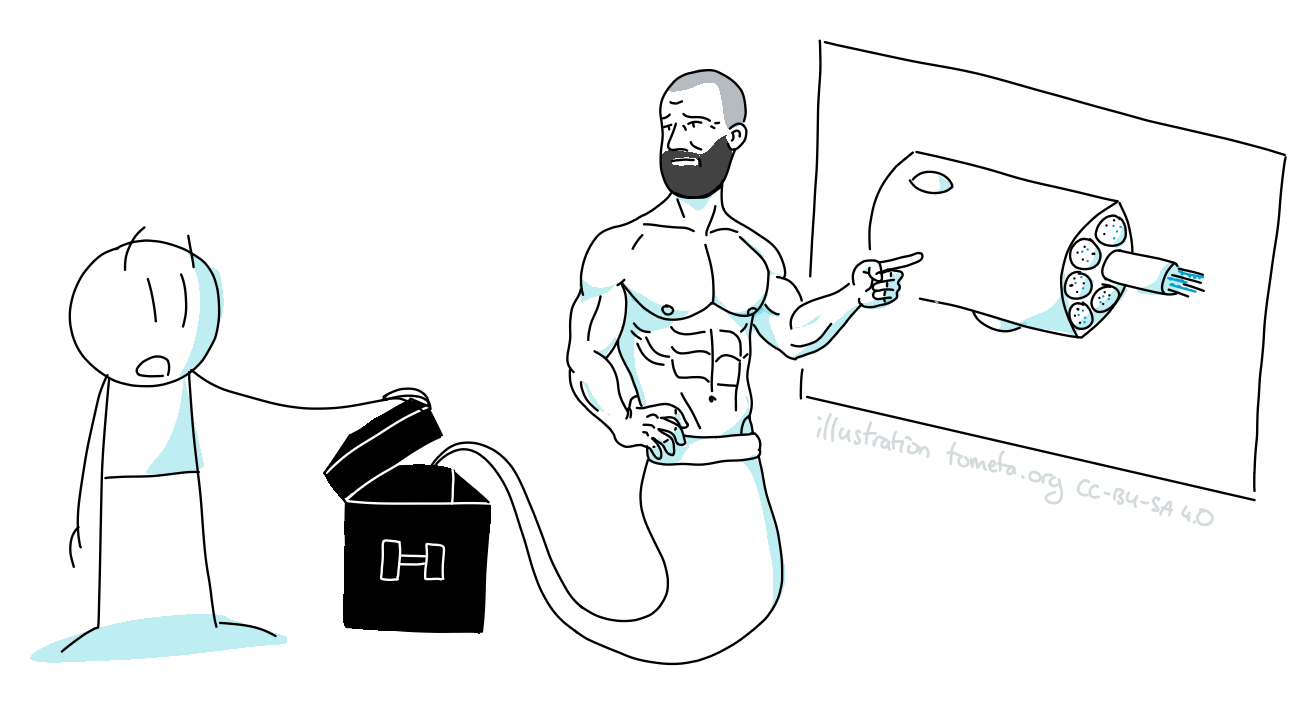

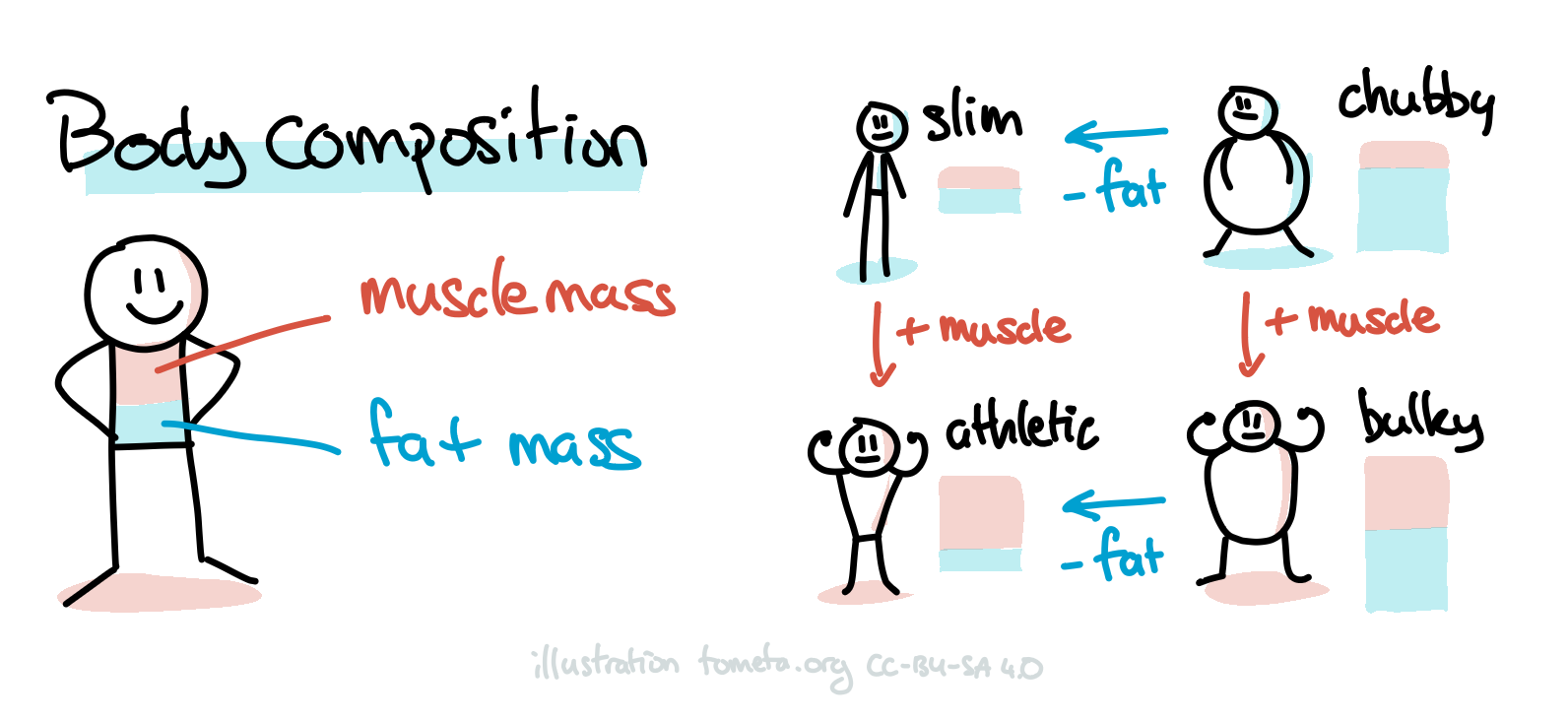

Body composition is the distribution of the body mass into roughly 2 categories : the fat mass and the lean mass (mostly muscle). There’s more nuance, but for our purposes this is enough.

Body composition seems to be a useful proxy when it comes to measuring general athleticism as it correlates well with health, performance and aesthetics metrics, more than generic metrics like Body Mass Index BMI.

[1, 2, 3]

Personally, I’ve always fallen into the “slim, hardgainer” category. Looking back, it makes sense: I had no idea what was happening under the hood, so I wasn’t doing the right things to actually change my body composition.

How does the body change?

-> By cells modifying their structure as an adaptation to external stimuli

Basically, the body maintains its structure unless it’s given a reason to change. In other words, my current body composition is simply the most adapted to what I regularly do. But if I change my lifestyle, the body will adapt to some extent.

Adaptation is a totally common thing in life. When I spend time at high altitude, my body produces more red blood cells to adapt to the low oxygen stimulus. If I have a very manual work, the skin of my hands will get thicker in the areas with the highest friction. Or when I learn a new language, my neurons rearrange to connect more efficiently. And these are mostly reversible when the adaptation isn't needed anymore.

One might argue that at the time of our hunter-gatherer ancestors, the need for physical fitness adaptation was greater than today (imagine running every day to find food, carrying loads back to the camp or performing long migrations). Nowadays, especially in rich countries, people live in physically "comfortable" environments (think of our elevators, cars, couches) that don't challenge our muscle cells. That's why we need physical training to voluntarily create stimuli that invite our bodies to adapt.

What makes the body adapt?

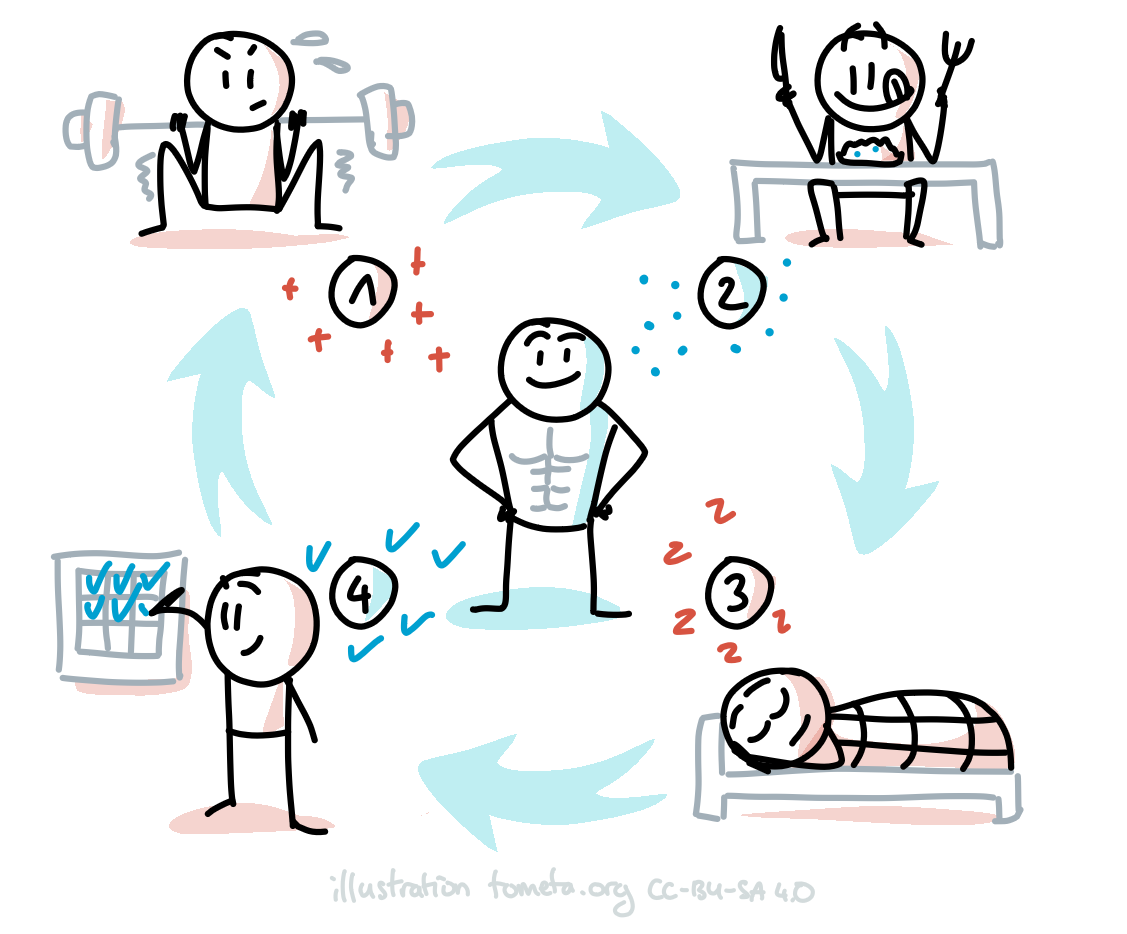

-> There is a simple formula for adaptation, it requires 4 elements:

- Adaptation signal (from training)

- Building blocks (from nutrition)

- Recovery time (rest and sleep)

- Repetition over time (consistency)

This formula is quite simple in theory but quite difficult to apply in practice as all the elements are important. Miss any of these, and progress stalls.

What made me fail in the past was mostly diet as I generally struggle to eat enough quantities to gain weight and consistency as I wouldn't manage to turn my workouts into long-term lifestyle habits.

Now, training for athleticism can mean many things and the adaptation required will vary depending on the objective. For example endurance athletes will apply a certain stimulus so that the cells adapt towards a better management of low tension sustained efforts. Equally, sports requiring explosivity, agility, speed, flexibility or pure strength will all involve slightly different cells, different stimuli and different adaptations.

In my case, as I want to improve my body composition I need to build more lean mass (on top of my other sports that develop specific athleticism). So I will now focus mostly on the muscular hypertrophy and strength type of adaptations. The word "hypertrophy" can be intimidating. I used to associate it with extreme competitive bodybuilding (which is not my objective), but it is actually a neutral term used in exercise science to simply describe the increase of the size of the muscles.

Also, in the rest of this post I will deep-dive specifically on the signaling part of the adaptation formula. I will touch briefly on the others (nutrition, recovery, consistency) but they would need their own full article.

How do muscles actually grow and become stronger?

-> By responding to the hypertrophy signal and synthesizing more muscle proteins in the fibers.

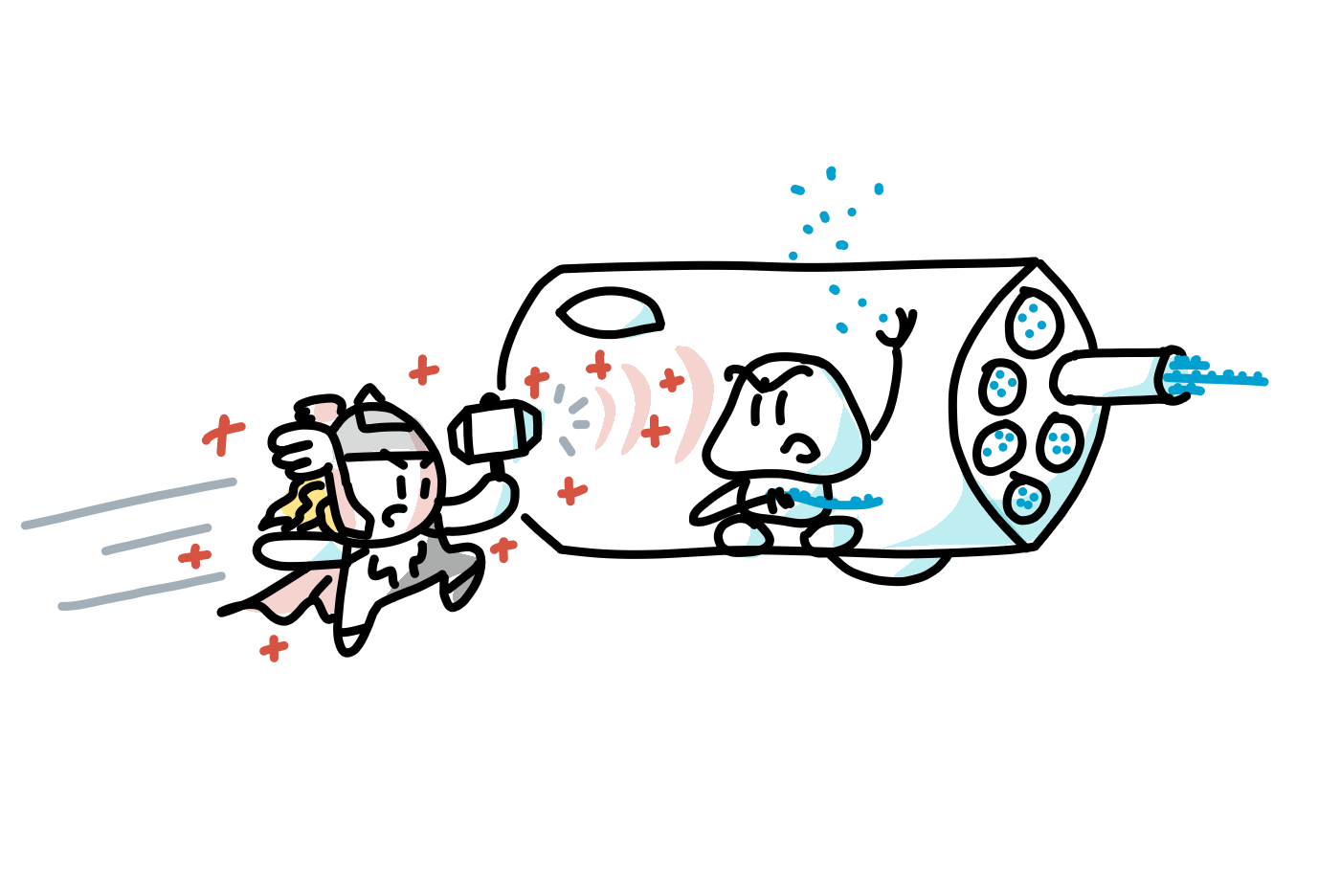

Muscle cells (also called muscle fibers) are very long tubes filled with even smaller tubes called myofibrils which are full of long proteins responsible for muscle contraction. These are called actin, myosin or troponin but whatever their names, these are the ones that we want the muscle cells to produce more of. And this happens if the cells get the hypertrophy signal (like "hey we struggled last time so let's make more proteins to be better prepared next time"). More of these proteins means bigger cells but also stronger cells (as there are more contractile units to deliver force).

I visually represent the growth signal as a "mini-Thor" hammering the cell because the main hypertrophy signaling molecule is called "mTOR". The actual signal is a complex cascade of biochemical reactions which I won't go into in this article but mTOR is the key player.

Oh, and this Goomba-like creature is a ribosome of the cell, it is responsible for producing the proteins.

Nutrition is an essential part of the process because if the cell doesn't have the right building blocks it cannot build more muscle proteins, and some of the building blocks (called amino acids) are particularly crucial. For example the one called Leucine is omnipresent in those long muscle proteins and is also necessary so that the hypertrophy signaling works properly. [10]

There are actually several types of hypertrophy, yes the muscle cells can grow and get stronger by adding more contracting proteins (called myofibrillar hypertrophy) but they can also kind of "swell" without adding more contractile units (called sarcoplasmic hypertrophy) - this type of hypertrophy doesn't come with strength gains but can be pursued for aesthetics purposes. Also a muscle might grow because the connective tissue - sort of the film in which the cells are wrapped - grows (called connective tissue hypertrophy).

Note, however, that muscle growth doesn't mean adding more muscle cells (I didn't know...).

Muscle atrophy is the opposite of hypertrophy. It means the shrinking of muscles. As we stop training regularly, the hypertrophy signal isn't generated anymore for the cells to need to maintain this level of muscle proteins. Because maintaining muscle is energetically costly (more than maintaining fat for example), the cells will break down the unnecessary proteins (since there is no need anymore for so much contracting power) and the muscles will decrease in size. This happens naturally as we age. [15]

How does training trigger and sustain the hypertrophy signal?

-> Through sufficient mechanical tension + fiber recruitment + progressive overload

- Mechanical tension

From the cell’s perspective, all hypertrophy training boils down to this: A load pulls on the fiber, the fiber contracts to resist, if tension is high enough, the fiber deforms, sensors inside detect this deformation (via a mechanism called mechanotransduction) and activate the hypertrophy signaling pathway. [4]

This is especially true during: eccentric actions (lengthening under load), and full range of motion movements (moving through the max joint angles). [4, 12, 13, 14]

Let's address the elephant in the room: what about "muscle damage and repair"? this is the common mainstream explanation for how muscles grow: "when we workout we create micro tears in the muscles so when we rest our body repairs it and add a little bit more that's how they grow". This is mostly outdated and oversimplified as far as I understand. Based on the latest scientific understanding, mechanical tension is the main driver for the growth response. And it doesn't require any actual damage. While some damage can occur at the cellular level during training, it is at best only adding to the signaling and at worst can interfere with hypertrophy because resources go to repair instead of protein synthesis. [4]

Without going into too much details, there is also something called metabolic stress (basically the accumulation of chemical byproducts in the cells when training leading to acidification, lactate production, reduced oxygen) these are stress signals for the cell that can also contribute to the growth response. Some training methods try to optimize this mechanism as well like occlusion training to reduce blood flow temporarily and maximize metabolic stress. But again this is happening anyway alongside the mechanical tension that's why I focus mainly on it.

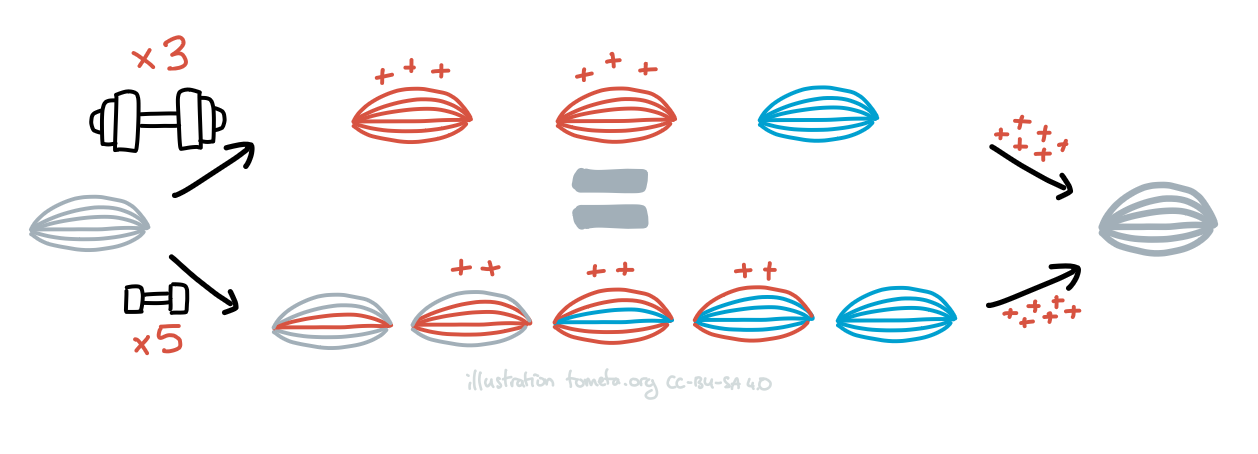

- Fiber recruitment

A whole muscle is composed of many individual muscle cells (about 50'000 per cm²) and they don't get always all activated. The muscle activates just the amount of fibers necessary to handle the specific load at hand. So when we want to grow a muscle we want to make sure that all of the fibers are "recruited", especially because the ones that are recruited last, are the ones who also tend to respond most to the hypertrophy signal.

There are actually several types of muscle fibers with quite different features in terms of size, fatigue resistance, force production and hypertrophy response. To me this is a fascinating aspect of the anatomy that explains why endurance athletes and bodybuilders can have very different morphologies despite both training their muscles a lot. I leave this aside for the moment and maybe I'll do a bonus deep-dive on muscle fiber types one day. What matters for us is that the fibers that grow the most are the ones recruited last.

Also here a quick note on exercise execution: it is super essential to perform the movement with "good form". Not only is it important to prevent injuries (and thus impacting the ability to sustain the training) but also in terms of fiber recruitment. As fatigue accumulates during a set, adding "cheat reps" usually means starting to engage other muscles than the ones primarily involved in the movement instead of recruiting more fibers from these muscles.

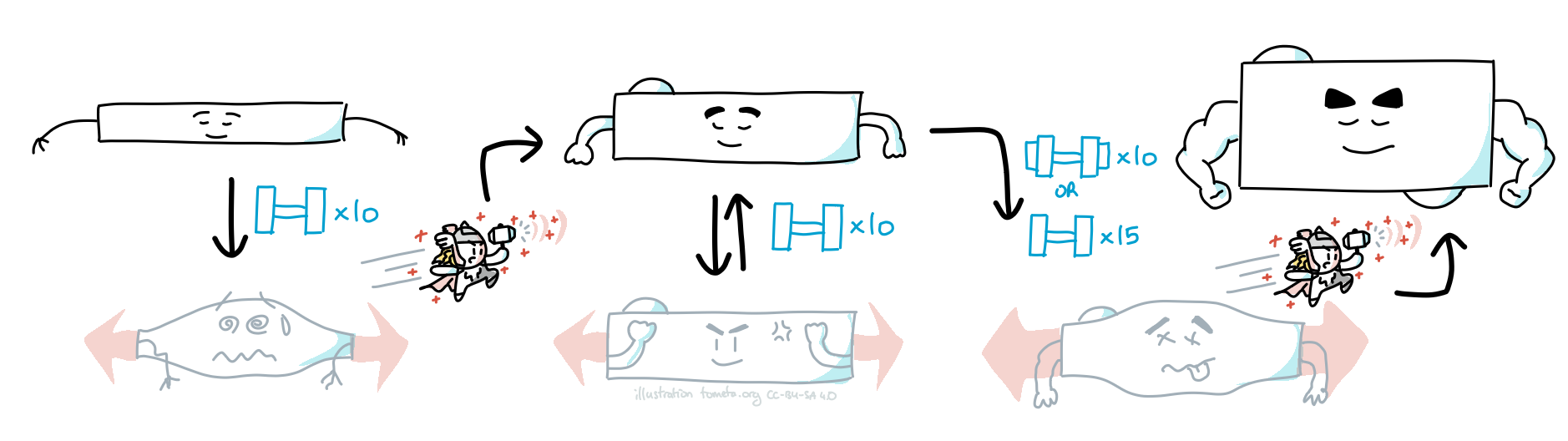

- Progressive overload

Any fitness enthusiast has heard the term. It simply means that as the body adapts, the training stimulus also has to evolve, otherwise the system has no reason to keep changing (which can be fine if the goal is just maintenance). The core idea is that for a muscle to continue growing, it must regularly experience a stimulus that’s beyond what it’s used to.

At the cellular level it means that the threshold for the activation of the hypertrophy signal increases as we get stronger. Remember our mini-Thor? He wakes up when the cells are getting bent and deformed under the load. But after he has done his job and the cells have grown and got stronger, this same load isn't deforming them anymore (that was the whole point of the adaptation in the first place!). So in order to keep growing more mechanical tension is needed to keep the signal active.

In traditional weightlifting, progressive overload mostly meant adding more weight to the bar or the dumbell. But one can increase the stimulus through other training variables like frequency (training more often), volume (performing more reps) or time-under-tension (e.g. slowing down the reps). [11, 16, 18]

If you're wondering what those bumps are on the surface of the cells as they grow, these are cell nuclei that gets added to the cell as a result of the hypertrophy signal. They come from adjacent so called satellite cells. This is another fascinating aspect of the muscle physiology that I won't explore further here.

What's the best training style based on these principles?

-> The million dollar question... and the fair answer is that there is no absolute "best". Although the "best for you" is probably simply... the one you can sustain. (I know... boring but true)

Training usually means performing a certain exercise for a certain number of reps and a certain amount of sets. Research seems to agree that good hypertrophy signal can be obtained by a wide range of training programs as long as they hit a weekly volume somewhere between 10 to 20 hard working sets (meaning challenging enough so that all fibers are recruited) and rep ranges can vary from 5 to 35. [8, 12, 19]

These are wide ranges! That’s why weightlifting, calisthenics, CrossFit, and various sports like martial arts can all work to build muscle. So at the end of the day the actual program choice boils down to other factors (personal preference, accessibility, injury risk, social component etc.).

To be even more blunt: As long as the programs are aligned with the above mentioned principles (of sufficient mechanical tension, fiber recruitment and progressive overload) in a context of adequate nutrition and recovery, the best one is the one you can keep on performing with consistency over time. As we've seen, because of the nature of how the body adapts, any time-bound program will generate time-bound results.

Part 2: An application of these principles

So far we've laid out the general principles of training to improve body composition by increasing muscle mass. Let's now look at one style of training in particular that applies these principles. Again I'm not pretending that it's better than any other but it happens to be the one I'm most able to sustain happily at the moment (it is based on Kboges' approach).

Application : High-frequency bodyweight workout

This training style is characterized by three elements: (1) low tension, (2) close-to-failure and (3) high frequency. It is a good approach for hypertrophy training while managing fatigue efficiently.

In other words: short, daily bodyweight workouts that recruit all muscle fibers without excessive fatigue.

Let's look at those few key components.

- Low-tension: Within a set, high reps with a lighter load (bodyweight) produces equivalent hypertrophy signaling to heavier weight lifting. And it comes with extra benefits in terms of accessibility and adaptability.

This has to do with the fiber recruitment principle we mentioned earlier: When lifting heavy weights, the intensity is so high that all the muscle fibers will likely activate right away and one will only be able to do a few reps before the whole muscles fatiguing (that's the typical gym style of training). When working out with the bodyweight (which is lighter) the first few reps will mostly be recruiting some of the fibers but as one gets close to failure, the mechanical tension builds up, the earlier fibers fatigue and the later ones (hypertrophy-sensitive) get activated to take over, leading to an equivalent hypertrophy signal. [5, 6, 7]

So for me choosing bodyweight over weightlifting boils down to other reasons like accessibility (no pricy gym membership, nor expensive bulky equipment) or adaptability (I can workout almost anytime anywhere).

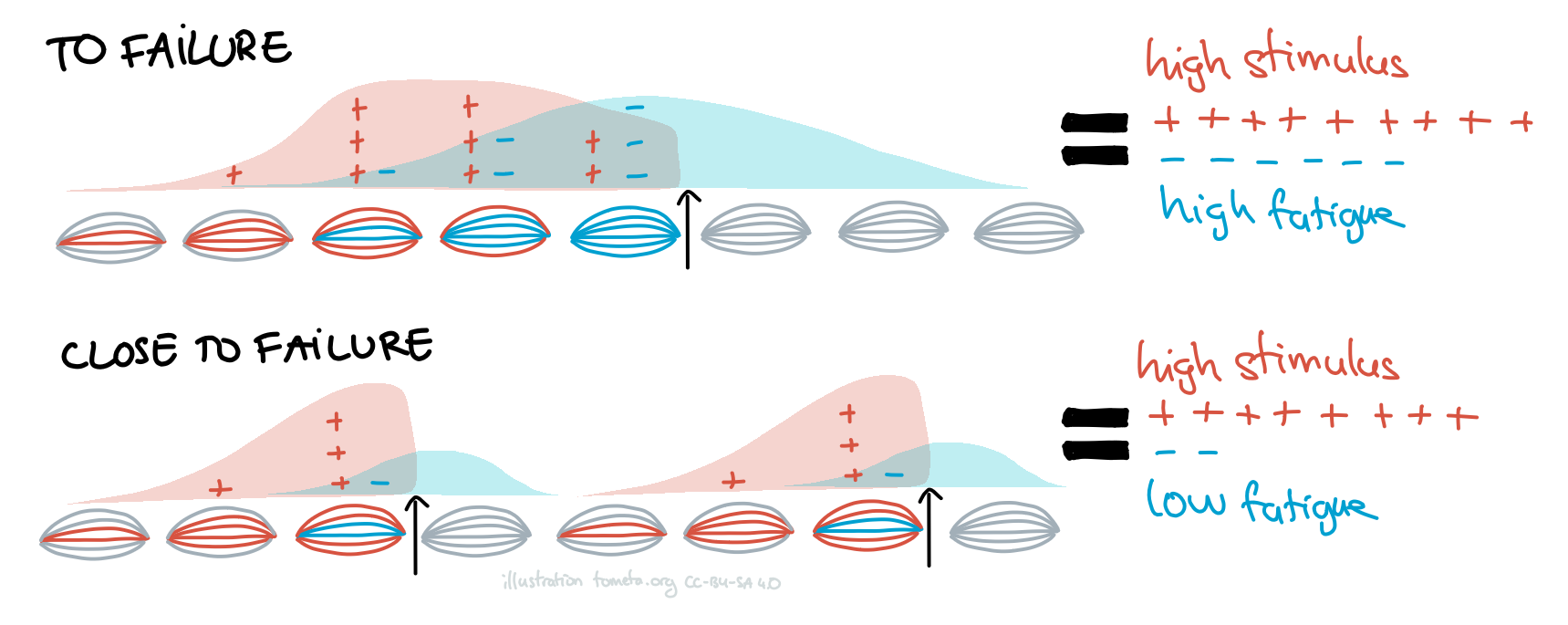

- Close-to-failure: Within a session, stopping a few reps shy of failure reduces fatigue, making it easier to complete more sets and stay consistent without compromising too much on the hypertrophy signal.

In terms of hypertrophy signaling, absolute failure might not be necessary and stopping the set a few reps shy of failure provides enough fiber recruitment and mechanical tension with the additional benefit of less fatigue build up and so the ability to perform more sets. [9]

Also, using “failure” as the reference point for how long a set should last is an effective built-in form of progressive overload. As the muscles grow and get stronger, the failure point naturally shifts. By consistently training close to that point, we automatically keep the stimulus high—something that fixed-rep schemes like “3×12” don’t always guarantee.

In the past I made the mistake of trying to systematically perform my sets to failure (meaning the moment where the body simply can't add a rep without sacrificing good form). But this was very taxing in terms of fatigue and often impeded my ability to do multiple high quality sets. Also as I'd tend to rest a bit longer to manage fatigue I'd get more chance to get distracted on my phone or else and thus risking to interrupt the workout before the end... (has happened more than once...)

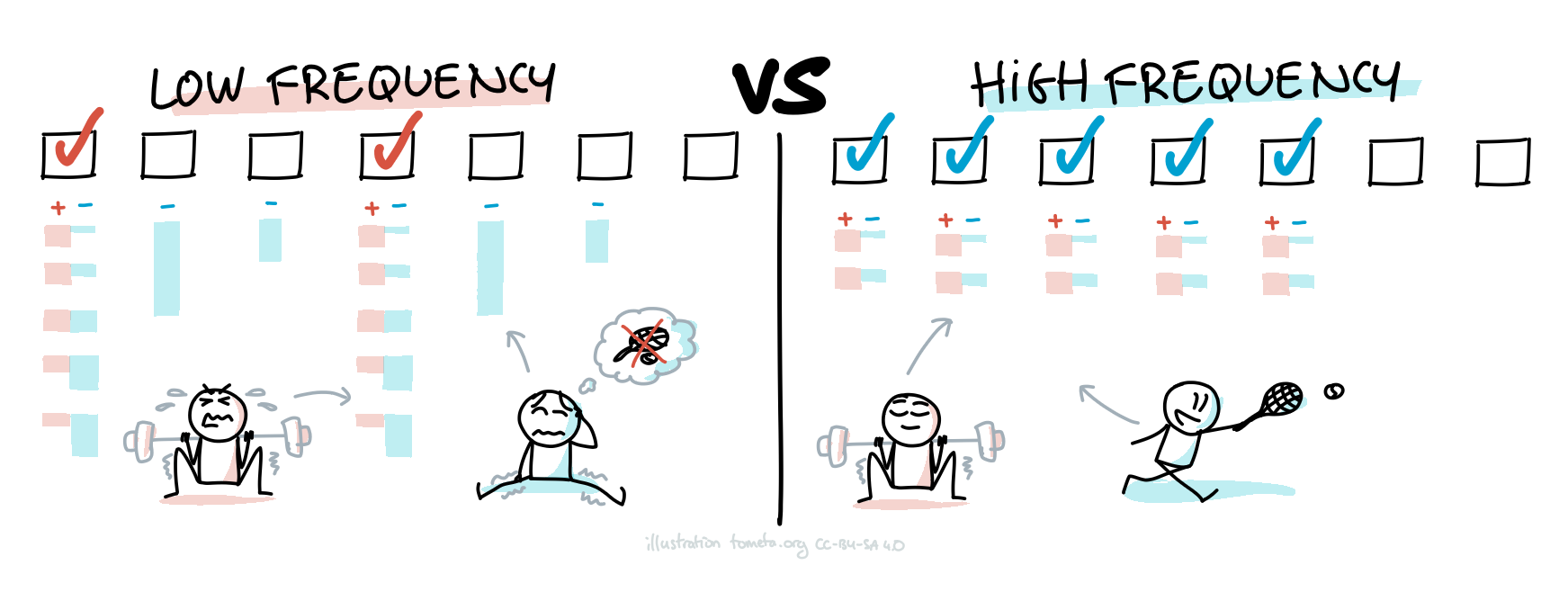

- High-frequency: Spreading sets across the week minimizes fatigue buildup and can be a better lifestyle fit for some people.

This has to do with the buildup of fatigue as the training session progresses. Physiologically when the muscles are exerted they fatigue. And even though the stimulus for the growth signal stops at the end of the set, the accumulated fatigue stays and a rest period is needed before going to the next set. Furthermore it seems that the first sets of a session provide the most stimulus while the later ones accumulate more fatigue which can then carry over to the next days. [11, 12, 17]

This is one of the biggest changes in my training. Before I was doing the classical 2-3 long training sessions (with many sets and many exercises) and often I'd notice it'd take me a day, sometimes two to recover, days where I wouldn't practice other hobby-sports. Or the other way around: when I knew I had another sports planned I'd skip the workout to avoid being tired but then in the long run I'd train less... Now I just do 1 or 2 sets of 3 or 4 exercises almost every day. And while the overall weekly hard set target remains the same, the volume is much more manageable and I have lower risk to lose motivation and skipping one day is easy to catch up within the rest of the week.

In summary :

- How to cultivate an athletic body (healthy, strong and aesthetic)?

-> Add more muscle to the body composition. The body changes, provided it gets sufficient adaptation signaling through training, appropriate building blocks from nutrition and this repeated consistently over time. - How does the body build muscle at the cellular level?

-> When receiving the hypertrophy signal the muscle cells respond by synthesizing more muscle proteins within the cells (and other adaptations). The muscle fibers thus get bigger and are able to produce more force the next time. - How does training generate the muscle growth signal?

-> When we exercise, we apply mechanical tension to the cells. This deforms their internal structures and triggers a biochemical pathway (aka the hypertrophy signal) telling the cell machinery to produce more muscle proteins. For a muscle to grow, all its fibers need to be recruited and the mechanical tension increased overtime to sustain the signal. - What type of training is suitable for hypertrophy and strength?

-> Many training styles and methods can trigger a good hypertrophy signal and it all comes down to personal preference and what style enables the most consistency. High frequency bodyweight training is an example of a low risk, accessible and flexible way to train that manages well fatigue making it a good candidate for lifestyle sustainable training.

Final note on what I didn't cover: There are more fascinating aspects of the human exercise physiology that I didn't mention:

- satellite cells involvement and muscle memory,

- muscle fiber types (fast/slow-twitch)

- energy management in the cells (ATP, glycogen, triglicerides etc.)

- neural adaptations,

- the role of hormones and vitamins (and more generally nutrition and supplementation for training),

- the impact of stress and anxiety (and more generally the recovery and rest),

- performance enhancing drugs (anabolic steroids, EPO etc.),

- genetic influences and gender differences,

and probably more...

These would require more deep-dives that I may or may not do one day^^

That's it for this one. Hope you enjoyed the read and the illustrations and learned a thing or two.

References

- Sedlmeier, A. M., Baumeister, S. E., Weber, A., Fischer, B., Thorand, B., Ittermann, T., ... & Leitzmann, M. F. (2021). Relation of body fat mass and fat-free mass to total mortality: results from 7 prospective cohort studies. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 113(3), 639-646.

- Fields, J. B., Merrigan, J. J., White, J. B., & Jones, M. T. (2018). Body composition variables by sport and sport-position in elite collegiate athletes. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 32(11), 3153-3159.

- Brierley, M. E., Brooks, K. R., Mond, J., Stevenson, R. J., & Stephen, I. D. (2016). The body and the beautiful: Health, attractiveness and body composition in men’s and women’s bodies. PloS one, 11(6), e0156722.

- Schoenfeld B. J. (2010). The mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and their application to resistance training. Journal of strength and conditioning research, 24(10), 2857–2872. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181e840f3

- Morton, R. W., Sonne, M. W., Farias Zuniga, A., Mohammad, I. Y., Jones, A., McGlory, C., ... & Phillips, S. M. (2019). Muscle fibre activation is unaffected by load and repetition duration when resistance exercise is performed to task failure. The Journal of physiology, 597(17), 4601-4613.

- Grgic J. (2020). The Effects of Low-Load Vs. High-Load Resistance Training on Muscle Fiber Hypertrophy: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of human kinetics, 74, 51–58. https://doi.org/10.2478/hukin-2020-0013

- Schoenfeld, B. J., Grgic, J., Ogborn, D., & Krieger, J. W. (2017). Strength and hypertrophy adaptations between low-vs. high-load resistance training: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 31(12), 3508-3523.

- Schoenfeld, B. J., Grgic, J., Van Every, D. W., & Plotkin, D. L. (2021). Loading Recommendations for Muscle Strength, Hypertrophy, and Local Endurance: A Re-Examination of the Repetition Continuum. Sports (Basel, Switzerland), 9(2), 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports9020032

- Refalo, Martin & Helms, Eric & Trexler, Eric & Hamilton, David & Fyfe, Jackson. (2022). Influence of Resistance Training Proximity‑to‑Failure on Skeletal Muscle Hypertrophy: A Systematic Review with Meta‑analysis. Sports Medicine. 53. 10.1007/s40279-022-01784-y.

- Kayleigh M. Dodd and Andrew R. Tee. 2012. Leucine and mTORC1: a complex relationship. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism 302:11, E1329-E1342 https://journals.physiology.org/doi/abs/10.1152/ajpendo.00525.2011

- Schoenfeld, B. J., Grgic, J., & Krieger, J. (2019). How many times per week should a muscle be trained to maximize muscle hypertrophy? A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies examining the effects of resistance training frequency. Journal of sports sciences, 37(11), 1286–1295. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2018.1555906

- Bernárdez-Vázquez, R., Raya-González, J., Castillo, D., & Beato, M. (2022). Resistance training variables for optimization of muscle hypertrophy: An umbrella review. Frontiers in sports and active living, 4, 949021.

- Douglas, J., Pearson, S., Ross, A., & McGuigan, M. (2017). Chronic adaptations to eccentric training: a systematic review. Sports medicine, 47(5), 917-941.

- Kassiano, W., Costa, B., Nunes, J. P., Ribeiro, A. S., Schoenfeld, B. J., & Cyrino, E. S. (2023). Which ROMs lead to Rome? A systematic review of the effects of range of motion on muscle hypertrophy. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 37(5), 1135-1144.

- Nunes, E. A., Stokes, T., McKendry, J., Currier, B. S., & Phillips, S. M. (2022). Disuse-induced skeletal muscle atrophy in disease and nondisease states in humans: mechanisms, prevention, and recovery strategies. American journal of physiology. Cell physiology, 322(6), C1068–C1084. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpcell.00425.2021

- Plotkin, D., Coleman, M., Van Every, D., Maldonado, J., Oberlin, D., Israetel, M., ... & Schoenfeld, B. J. (2022). Progressive overload without progressing load? The effects of load or repetition progression on muscular adaptations. PeerJ, 10, e14142.

- Sousa, C. A., Zourdos, M. C., Storey, A. G., & Helms, E. R. (2024). The Importance of Recovery in Resistance Training Microcycle Construction. Journal of human kinetics, 91(Spec Issue), 205–223. https://doi.org/10.5114/jhk/186659

- Azevedo, P. H. S. M., Oliveira, M. G. D., & Schoenfeld, B. J. (2022). Effect of different eccentric tempos on hypertrophy and strength of the lower limbs. Biology of sport, 39(2), 443–449. https://doi.org/10.5114/biolsport.2022.105335

- Baz-Valle, E., Balsalobre-Fernández, C., Alix-Fages, C., & Santos-Concejero, J. (2022). A systematic review of the effects of different resistance training volumes on muscle hypertrophy. Journal of human kinetics, 81, 199.